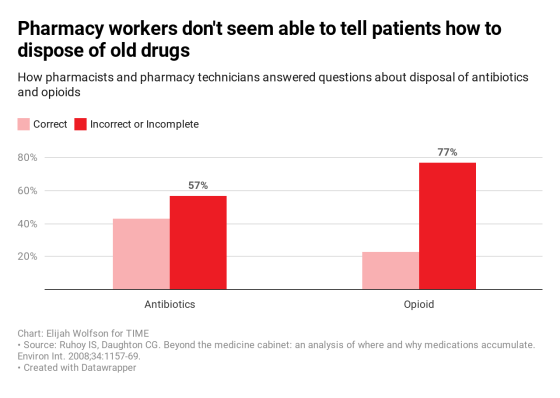

Today (Dec. 30), a team of researchers from the University of California, San Francisco and the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., published the results of an investigation into whether or not pharmacy workers could provide accurate information on the disposal of two classes of drugs: opioids and antibiotics. The results are frightening:

The researchers enlisted volunteers to place calls to nearly 900 pharmacies in California, posing as parents with leftover antibiotics and opioids from a “child’s” recent surgery. They asked the pharmacy employees on the line—either pharmacists or pharmacy technicians—how to deal with these unused drugs, and then the researchers compared those answers to the guidelines for correct disposal published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The found that approximately 43% of pharmacy workers responded accurately on how to deal with antibiotics; just 23% knew what to do with opioids.

Drug disposal is one of those vexing problems where people generally want to do the right thing, but often simply don’t know how. As Hillary Copp, associate professor of urology at UCSF and the senior author of the study noted in a press release, “The FDA has specific instructions on how to dispose of these medications, and the American Pharmacists Association has adopted this as their standard. Yet it’s not being given to the consumer correctly the majority of the time.”

According to the FDA, unused medications should be put (without crushing any pills or capsules) in an “unappealing substance such as dirt, cat litter, or used coffee grounds;” that mixture should then be put into a sealed container like a secure plastic bag before it is thrown out. In addition, all personal information should be scratched out or otherwise destroyed.

Indeed, in 2017, a team of scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and Environmental Protection Agency published a paper reporting the results of a study of 38 streams across the country. It found 230 human-created drugs and poisons. And there are significant knock-on effects of improper disposable: many of the drugs identified in the 2017 study are known to kill, harm the health of, or change the behavior of fish, insects and other wildlife. This, in turn, can impact the food chain, and eventually harm humans as well.

Antibiotics and opioids, the two drug classes that the Annals of Internal Medicine study looked at, are particularly malevolent when not disposed correctly.

When antibiotics are disseminated widely throughout the environment, it raises the chances of bacteria developing resistance to the drugs. Any bacteria that encounters an antibiotic, whether in the human body, or in a stream or pond, will attempt to survive. Those that do will pass their genes onto future generations of bacteria, fueling a growing global health concern: the World Health Organization has made it clear that antimicrobial resistance in microbes (which includes antibiotic-resistant bacteria), is one of the globes biggest impending public health challenges, given that it could eliminate some of medical science’s most effective tools against disease-causing organisms.

Meanwhile, research into the impacts of opioids on lab animals suggests that they respond to the drugs much like humans: by self-administering over and over, to their detriment. Scientists are still working on understanding how opioids in the waste stream impact animals living in the wild. One thing is for sure: opioids ARE in the global water supply. A 2018 review of the scientific literature found 22 opioids in wastewater and surface water samples from all over the world.

Perhaps the bigger issue with opioids, however, is that those prescribed them tend to keep them around. The results of a survey published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 2016 found that about 60% of Americans prescribed opioids kept their leftover meds for “future use,” and a number of recent studies and investigations have found that these drugs, when either shared with or surreptitiously taken by relatives and acquaintances, can lead to addiction and overdose.

On the flip side, other recent studies have noted that clearer guidance and take-back events can get people to not only get rid of unused opioids, but to do so in a way that’s environmentally sound. Given the ongoing American opioid crisis, any steps to get this class of deadly drugs off the street—and out of medicine cabinets—could be significant. This most recent study suggests that one place to start might be at the point-of-sale: the pharmacy.