2020 was a year of extreme weather around the world. Hot and dry conditions drove record-setting wildfires through vast areas of Australia, California and Brazil and Siberia. A record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season landed a double blow of two hugely destructive storms in Central America. Long-running droughts have destroyed agricultural output and helped to push millions into hunger in Zimbabwe and Madagascar. A super-cyclone unleashed massive floods on India and Bangladesh.

And overall, 2020 may end up the hottest year on record—despite a La Niña event, the ocean-atmospheric phenomenon which normally temporarily cools things down.

Though it’s historically been difficult to say if single weather events were directly caused by climate change, scientists have proven that many of the events that took place in 2020 would have been far less likely, or even impossible, without changes to the climate that are being driven by the warming of the Earth.

Thanks to increasing levels of heat-absorbing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, global average temperatures last year were 1.15°C over the pre-industrial era. Depending on how quickly we can reduce our emissions of these gases, the global average temperature increase is expected to be anywhere between 1.5°C and 5°C by 2100. While emissions dipped briefly during the first COVID-19 lockdowns, they have now rebounded to close to 2019 levels.

A rise of a few degrees may not sound like much, but it has huge implications for the weather we’ll see in the coming years, says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA focused on the links between climate change and extreme weather. “It’s a number that is describing really profound and vast changes in the climate system that we feel mostly through individual weather events and through extreme events.”

It’s impossible to know if 2021 will be as record-breaking as 2021, but it’s highly likely that more extremes are on the way. “From one year to the next, there’s still a lot of random variation superimposed on top of the long term trends,” Swain says. “While 2020 may have been a particularly extreme year in contrast to individual years in the past, scientifically and looking forward, what’s more meaningful is that 2020 was not really an aberration.”

Here’s what to expect from the climate next year—and what is likely to happen with the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving the changes.

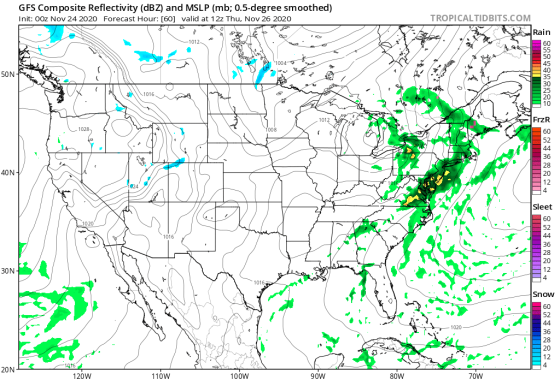

Hurricanes and storms

2020’s Atlantic hurricane season saw a record number of 30 named storms, including 13 hurricanes. In September, Hurricane Sally battered Florida and Alabama, cutting power to more than half a million homes. In November, Hurricanes Eta and Iota hit Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and other Central American countries in close succession, submerging towns, destroying infrastructure and farmlands, and killing dozens across the region.

Climate scientists aren’t sure if climate change will cause an increase in the number of hurricanes generally. But climate change is affecting the characteristics of hurricanes and making them more destructive. They are likely to be more intense, carrying higher wind speeds and heavier rains, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Read more: Central American Leaders Demand Climate Aid as a Record Storm Season Batters the Region

This year’s very active hurricane season was in part driven by La Niña, the ocean-atmospheric phenomenon, a counterpart to El Niño, which results in temporarily lower ocean surface temperatures across the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean and atmospheric changes, creating favorable conditions for hurricanes.

Early predictions for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season published by meteorologists at Colorado State University suggest there is a 6 in 10 chance that the season will be very strong or above average.

High temperatures, wildfires and droughts

Globally, 2020 is currently tied with 2016 as the warmest year on record. Even if it takes second place, that is remarkable given the occurrence of La Niña this year, which tends to lower temperatures, and the fact that 2016 was an El Niño year, when temperatures are generally warmer.

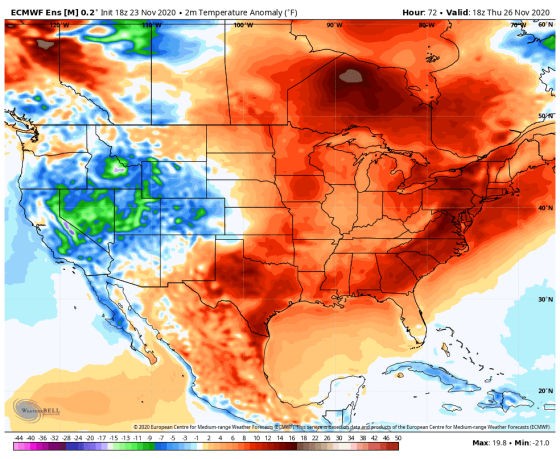

There is reason to believe that 2021 may be slightly cooler, says Swain, since La Niña conditions are expected to continue through to March. “It may be that some of the cooling effect of this La Niña will be felt a little bit more next year than this year. But it’ll still be quite likely to be among the top five warmest years on record, because we just aren’t really seeing we just aren’t really seeing any of the kinds of cooler years that we saw even 30 or 40 years ago anymore.”

La Niña doesn’t affect the whole of the U.S. in the same way. It tends to lower winter temperatures in the northwest of the country, and increase them in the southeast. In its outlook for winter, up to the end of February, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted below average precipitation and a worsening of drought conditions across many southern states.

We are likely to see more episodes of extreme heat than we are used to in the coming years, scientists say, because they have been made far more likely on a warming planet. Studies found that climate change made Europe’s 2019 heatwave up to 100 times more likely, for example.

When high temperatures combine with dry conditions, strong winds and an abundance of vegetation as fuel, wildfires become highly likely. In January, Australia’s record-breaking temperatures and prolonged droughts drove bushfires burned more than 27 million acres across the country, and destroyed thousands of homes. California’s 2020 wildfires burned more than 4 million acres by October, double the state’s previous record.

Again, it’s impossible to know if 2021 will beat the new records set in 2020. But it’s clear that increased wildfires are a part of our future. A group of California-based scientists, including Swain, found that since the early 1980’s, climate change had doubled the frequency of days with extreme fire weather in Autumn in the state. Previous studies have shown that fire seasons are getting longer as the world heats up.

Arctic melting

2020 was the second biggest year for Arctic ice melting after 2012—which is considered an outlier because of a destructive late-season cyclone. Worryingly, scientists say 2020’s sea ice melt followed a similar trajectory to 2012, without any such storm. And this was the first year since records began that Arctic sea ice had not started to freeze over by late October.

Read more: ‘A Climate Emergency Unfolding Before Our Eyes.’ Arctic Sea Ice Has Shrunk to Almost Historic Levels

The Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet, with a one degree rise in the average yearly temperature every decade for the last 40 years. As a result, scientists say we are likely to see increasingly faster melting and slower freezing each year. By 2035, a study published this August in Nature Climate Change found, it is likely that the Arctic ocean will be ice-free in summer.

Carbon emissions

When it comes to the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving the changes we are seeing in our climate, 2020 has been an anomaly. Global emissions of carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas, reached a new peak in 2019 – though they were just slightly above 2018 levels, raising hopes that emissions were levelling off. But this year they are expected to fall by up to 7% as a result of the drops in activity during the first COVID-19 lockdowns in March and April.

Coincidentally, 7% is the amount by which the U.N. says we’d need to cut carbon emissions every year for the next decade in order to keep in line with the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep global average temperatures from increasing more than 1.5°C over the pre-industrial era.

But we shouldn’t expect the reductions to hold in 2021, says Glen Peters, research director at the Oslo-based Center for International Climate Research. “A few months ago, I would have expected that it would take a few years to slowly edge back to 2019 levels. And hopefully, during that time, emissions reductions would start to take effect,” he says. “But now, the monthly data suggests that emissions have almost come back to 2019 levels now.”

With governments likely to spend large amounts of money to get economies going again, Peters says emissions are likely to bounce back quite strongly. He expects emissions in 2021 to be roughly the same as in 2019.

But the nature of recovery packages that governments roll out will be decisive to the trajectory of emissions—and climate change—longer-term. If these packages are green, and include lots of stimulus for renewable energies like solar, for example, they’ll give you a spike in emissions next year to build all the solar, and you would reap the benefits in the years later,” Peters says. “It’s a question of whether the recovery packages set future reductions in motion.”