A version of this article also appeared in the It’s Not Just You newsletter. Sign up here to receive a new edition every Sunday.

CHASING RAINBOWS (AND VACCINES)

We humans are notoriously unreliable, superstitious narrators, always scanning the horizon for signs that validate what our hearts have already told us. Take me, for example. I keep telling people I was vaccinated at Hogwarts’ Manhattan campus under the waxing moon (it was a gibbous moon to be exact). How auspicious!

Ok, so my COVID-vax site was really The City College of New York. But stepping through its big old gothic gates to receive a blessing of science was wondrous, maybe a little spiritual. There was even a rainbow-y halo around that big moon, another lucky omen if you’re hungry for such things.

I started digging for lore on moons and rainbows and learned that the physics of rainbows doesn’t detract from the mythical place they have in our cultural imaginations. In fact the opposite.

Just ask Steven Businger, professor and chair of Atmospheric Sciences Department at University of Hawai’i in Manoa. He’s a co-creator of RainbowChase, an app that alerts users when nearby conditions are conducive to rainbow sightings. And after decades in a state where mind-blowing rainbows are a daily occurrence, Businger still pulls over to take photos of them. “I’m completely spiritually gobsmacked by rainbows,” he says.

Most of Businger’s research has to do with hazardous weather, storm evolution, and forecasting. But in this pandemic year, he went on a bit of a glorious tangent to look at the science and mythology behind Hawaii’s prolific rainbows, which he posits are the most spectacular on Earth thanks to the state’s unique geography and weather patterns.

“The Hawaiians thought the rainbow was a path to a higher dimension, and in a real sense, it is,” says Businger.

<strong>The rainbow plays with our consciousness, and it’s a beautiful interplay. You look at it, you meditate, and boom, you’re in touch with a higher dimension</strong>.

The idea of the rainbow as a source of life, or a bridge to another plane, is embedded in cultural traditions across the world, from the ancient Greek rainbow goddess Iris to Aboriginal people of the desert’s stories of the Rainbow Serpent and the mythical Norse rainbow bridge to the land of the gods, Bifrost.

If you’re new to It’s Not Just You, subscribe here to receive a fresh edition every Sunday.

In Businger’s March 11 article, “The Secrets of the Best Rainbows on Earth,” he points out that there are more than a dozen different words for rainbow in Hawaiian. There are Earth-clinging rainbows (uakoko), standing rainbow shafts (kāhili), and barely visible rainbows (punakea).

There is also something called a moonbow, or lunar rainbow, a rare event in which the moon refracts light through water droplets in the air creating a kind of rainbow, similar to what the sun does.

And alas, Businger tells me that the colors I saw in the halo around the moon at City College were a moonbow which, like a rainbow, is only seen when the moon or sun is behind you.

What I likely saw on my way to get my coronavirus vaccine was a gorgeous lunar corona. And with that, I rest my mystical case.

Unfolded by rainbows are the faces of the flowers.

–Hawaiian proverb

Check out Steven Businger’s interview on Science Friday for more rainbow science.

If you’re new to It’s Not Just You, SUBSCRIBE HERE to receive an essay every Sunday.

And write to me at: Susanna@time.com

COPING KIT ⛱

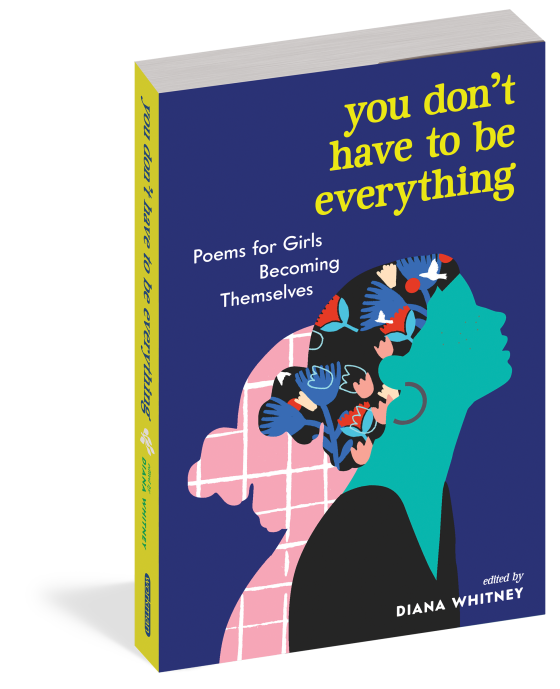

<strong>The sun’s white winds blow through you, there’s nothing above you, you see the earth now as an oval jewel, radiant & seablue with love.</strong>you don’t have to be everything Poems for Girls Becoming Themselves is a gift-worthy collection of 68 poems organized by emotion including works by Amanda Gorman, Sharon Olds, and Margaret Atwood.

―Margaret Atwood, Flying Inside Your Own Body

<strong>Empathy is a superpower, most especially in the workplace. It builds connection, makes for less dysfunction, and helps you find your way to the right purpose</strong>.EMPATHY FOR CHANGE is a new guide to cultivating empathy in thought and action, and why it’s an essential 21st-century skill. Author and former White House entrepreneur-in-residence Amy J. Wilson writes:

EVIDENCE OF HUMAN KINDNESS❤️

Here’s your weekly reminder that creating a community of generosity elevates us all.

The Antidote to Pandemic Loneliness

<strong>These strangers saved my life.</strong> </span><strong><span data-preserver-spaces="true">In a few weeks, I received thousands of emails and had regular pen pals…people who told me that I mattered and filled my heart with hope and joy. I no longer felt so alone. I realized that everyone feels the way that I did at some point</span></strong>.<span data-preserver-spaces="true">

Denise, a 37-year-old woman from Phoenix, wrote Pandemic of Love last May that being quarantined made her realize how alone she was. She began to wonder if anyone would even notice if she disappeared. POL Founder Shelly Tygielski called her to check-in. Then Tygielski asked her Instagram followers to “FLOOD a special email address with letters for Denise telling her she matters, that she is important, beautiful, and SEEN.” Denise has since received more than 3,000 emails via lovelettersfordenise@gmail.com. She writes:

Story and images courtesy of Shelly Tygielski, founder of Pandemic of Love, a grassroots organization that matches volunteers, donors, and those in need.

COMFORT CREATURES 🐕 🐈

Our weekly acknowledgment of the animals that help us make it through the storm.

Meet PEACHES submitted by MARY, who didn’t intend to get a puppy, but now isn’t sure she would have made it through these surreal times without her.